Women at Work on the Clyde in World War One

Although traditionally viewed as men’s work, during both World Wars women worked in ship and engineering yards along the Clyde.

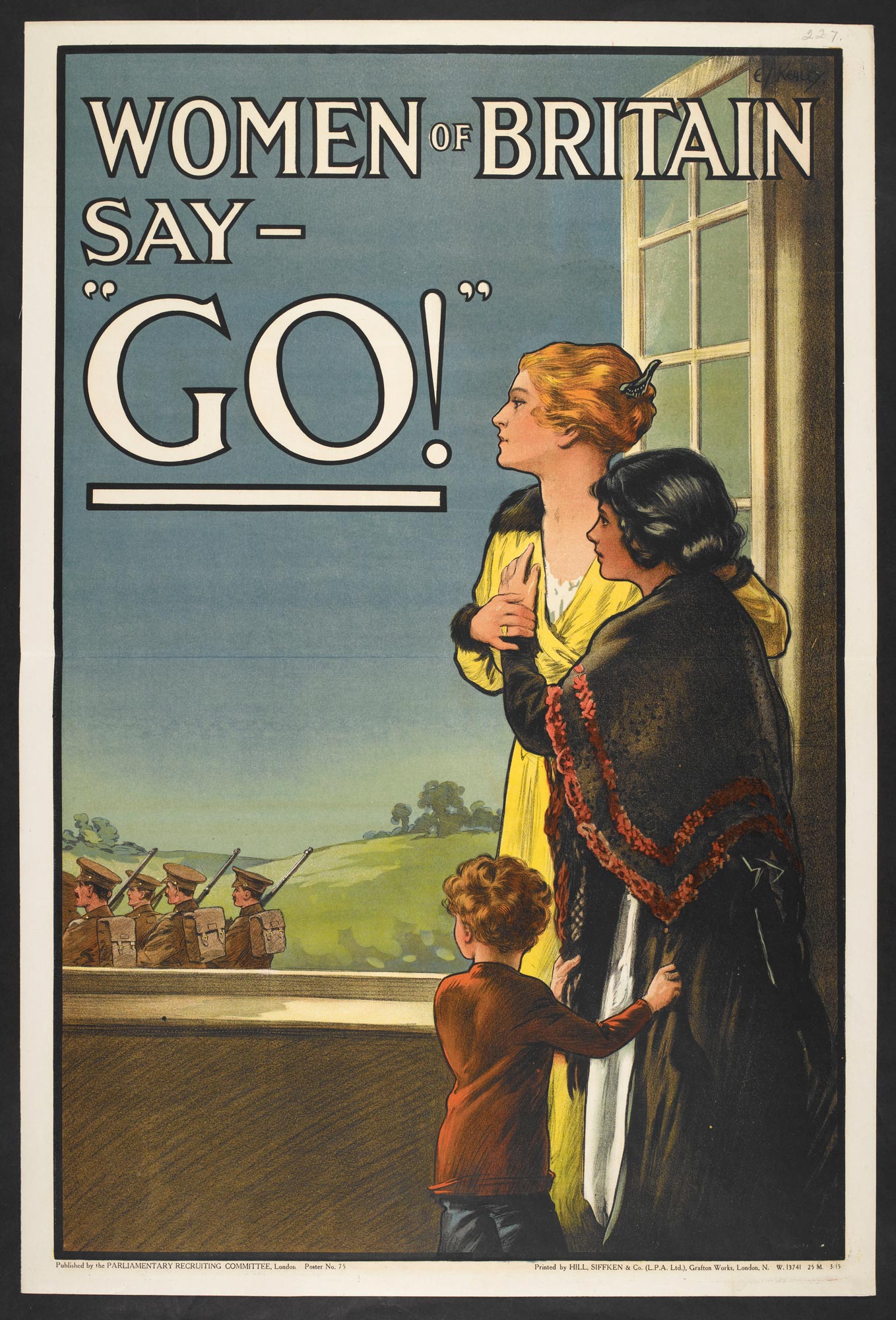

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 saw 22,000 Glasgow men and boys enlist in the army in the first week. In 1916 the British Government introduced conscription, and by 1918 200,000 had enlisted or been conscripted. This meant there was a serious shortage of labour along the Clyde. Suddenly shipyards were facing enormous pressure to produce ships for war but were struggling to find workers. The Government’s answer was ‘Dilution’ - employing women to boost the workforce numbers. Between 1914 and 1917 Clydeside shipyards manufactured an incredible 481 ships, a figure only possible with the employment of women.

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 saw 22,000 Glasgow men and boys enlist in the army in the first week. In 1916 the British Government introduced conscription, and by 1918 200,000 had enlisted or been conscripted. This meant there was a serious shortage of labour along the Clyde. Suddenly shipyards were facing enormous pressure to produce ships for war but were struggling to find workers. The Government’s answer was ‘Dilution’ - employing women to boost the workforce numbers. Between 1914 and 1917 Clydeside shipyards manufactured an incredible 481 ships, a figure only possible with the employment of women.

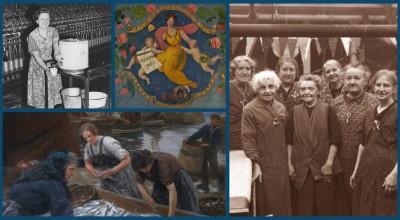

Prior to World War I it was unthinkable that women could work in shipyards - they traditionally worked in domestic roles or textile factories - but by 1918 30,000 women were employed in Clydeside industries. This was a level of economic freedom never experienced previously, but they were still not treated as equal to men. Employers were only obliged to pay women 75% of a man’s wage for the same job, but some unscrupulous companies would pay as little as 50%.

Dilution was not popular with the Unions, who encouraged their members to strike against it. In part this was because women were paid less, and the Unions believed that manufacturers would prefer to employ cheaper female labour after the war ended.

In 1916 Union and socialist agitators opposing Dilution were deported or imprisoned, and dilution continued regardless, but under the promise that the women would have to give up their jobs for the men when they returned from war.

A Space in the Workplace

As workers, employers, government and society adjusted to the idea of women workers there were practical considerations as to what work women could do.

In the engineering and shipbuilding industries there was particular debate about the physical capability of women to achieve the same work as a man, but women proved themselves up to the task and in the end turned their hand to many areas of shipbuilding:

“Attending plate-rolling and joggling machines. Back-handing angle irons. Flanging. Fitting, upholstering, and polishing. Drillers’ and caulkers’ assistant, Plumbers’ assistants. Platers’ helpers. Rivet heaters. Holders-on. Crane driving. Catch girls/ Firing plate furnace. General labouring …”

One woman working at Fairfield’s Shipyard wrote to her husband: “We were told that the amount of work we do in three weeks would have taken the men three years & Jamie the men are quite mad at us.”

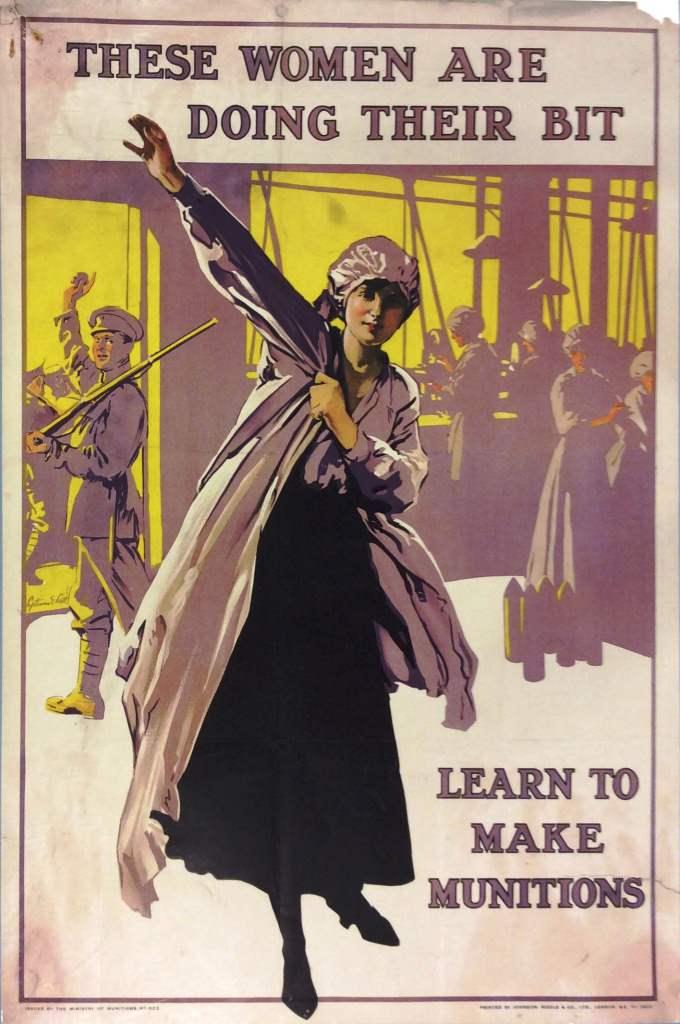

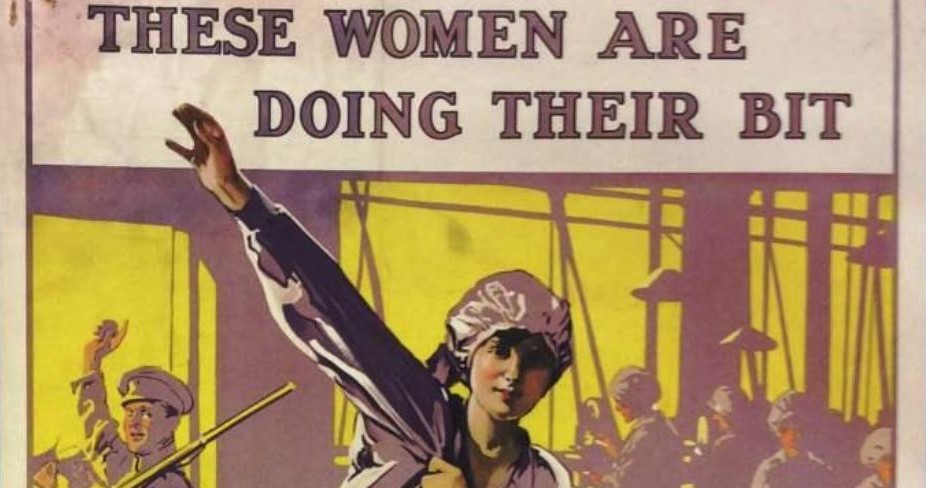

The employment of women also meant employers were forced to improve standards for all workers, introducing seating areas, canteens, and better lavatories. Women working was also propaganda – the national press presented it as an expression of patriotism during war, and it captured the public imagination. During wartime Glasgow’s McLellan gallery held an exhibition of photographs of women working, and a later exhibition of women demonstrating manufacturing skills - both attracted tens of thousands of curious visitors.

When the war ended many of the steps for working equality for women were rolled back. Women were forced out of their jobs and many were recruited into domestic service, unable to work in heavy industry and shipbuilding until the next World War.