Gaelic in Auchindrain

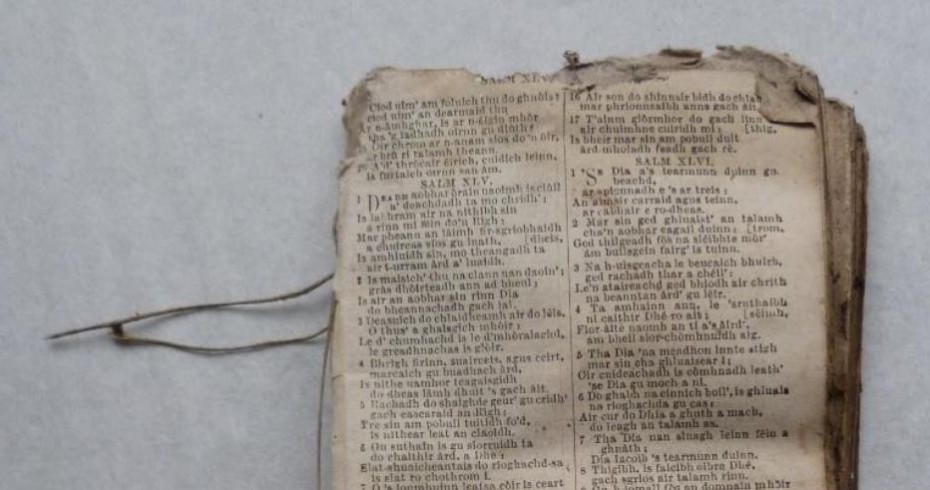

In 2012, part of a much-thumbed Gaelic Bible was found in Eddie’s House at Auchindrain, tucked into a gap in the wall above the kitchen sink along with some sheets of newspaper from 1937. Maybe not the obvious thing to use to stop a draught, but out of respect for Holy Scripture the book could not have been burned or thrown away.

1937 marked a year of change for Auchindrain. The township’s oldest resident, Duncan “Stoner” Munro, died at the age of 80, and soon afterwards his son Cally moved away with his young family, leaving Eddie MacCallum as the only tenant. With the departure of the Munros, there was no-one left with whom Eddie could speak Gaelic. Recent research suggests that the gradual shift from Gaelic to English was slower to happen in Mid-Argyll and Kintyre than elsewhere. The 1891 data for Auchindrain suggests a bilingual community, but the descendants of Auchindrain families argue that most still preferred Gaelic over English. Indeed, according to Cally Munro’s daughters their father did not learn English until he went to school, because his father, Duncan “Stoner”, preferred to speak Gaelic. But by the 1930s few children were learning and using the language and of those that did, most would never gain the same fluency as their ancestors.

In the 6th and 7th centuries, Argyll was part of the Dál Riata, a Gaelic overkingdom which spanned most of the west coast of Scotland and parts of Ulster. During this time the Proto-Celtic language of the British Isles is thought to have shifted through contact with the Gaelic-speakers of Ireland to become an early form of Scottish Gaelic. The language then spread to the rest of the Highlands and by the 10th century was the dominant language in northern and western Scotland. But not for long. King Malcolm Canmore (1031–1093) and his wife Princess Margaret of Wessex (1045–1093), introduced Anglo-Saxon culture to the Scottish court and refused to speak Gaelic. A process of gradual decline continued under later kings, and by the 15th century Gaelic had ceased to be the dominant language of the aristocracy and merchants, although most of the common people still held on to the old language.

Over time, Gaelic continued to be supplanted by Scots and was pushed back to the west coast and the Hebrides. Monolingual communities found themselves struggling, as Gaelic ceased to be the language of business and trade, as well as of the law. Dislocation and emigration of people during the Highland Clearances of the 18th and 19th centuries caused the number of Gaelic-speakers to progressively fall. Another severe blow came with educational policies that characterised English as the language of “civilised people”. From 1874 Gaelic was banned from schools and increasingly stigmatised as “primitive and uneducated”. It hung on in poetry, song and story, and as the predominant language in the islands of the west, but by the 1891 census was spoken by a mere 6% of the population.

From the 1960s the mood changed, and Gaelic began to be celebrated and encouraged as part of Scotland’s national identity. In 2005 the Scottish Government introduced the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act which for the first time gave Gaelic equal status in law to English, whilst the establishment of Bòrd na Gàidhlig was intended to help reverse the effects of the past suppression of Gaelic. Reactions to these schemes have been mixed. In an opinion piece in The Guardian in December 2010, the author expressed his discontent with the revival of Scottish Gaelic. He saw revivalist schemes as a token of a distant history, and criticised the money spent on the initiative. Others, however, feel that government action so far has not been nearly enough to build a sustainable future for one of Scotland’s historic languages. Today, although the Gaelic dialect of Mid Argyll can occasionally be heard spoken in Bail’ Ach’ an Droighinn – Auchindrain Township - by passionate enthusiasts who have reconstructed it from research and fragments of memory, but the everyday language is the English of the cultural conqueror.

From the 1960s the mood changed, and Gaelic began to be celebrated and encouraged as part of Scotland’s national identity. In 2005 the Scottish Government introduced the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act which for the first time gave Gaelic equal status in law to English, whilst the establishment of Bòrd na Gàidhlig was intended to help reverse the effects of the past suppression of Gaelic. Reactions to these schemes have been mixed. In an opinion piece in The Guardian in December 2010, the author expressed his discontent with the revival of Scottish Gaelic. He saw revivalist schemes as a token of a distant history, and criticised the money spent on the initiative. Others, however, feel that government action so far has not been nearly enough to build a sustainable future for one of Scotland’s historic languages. Today, although the Gaelic dialect of Mid Argyll can occasionally be heard spoken in Bail’ Ach’ an Droighinn – Auchindrain Township - by passionate enthusiasts who have reconstructed it from research and fragments of memory, but the everyday language is the English of the cultural conqueror.

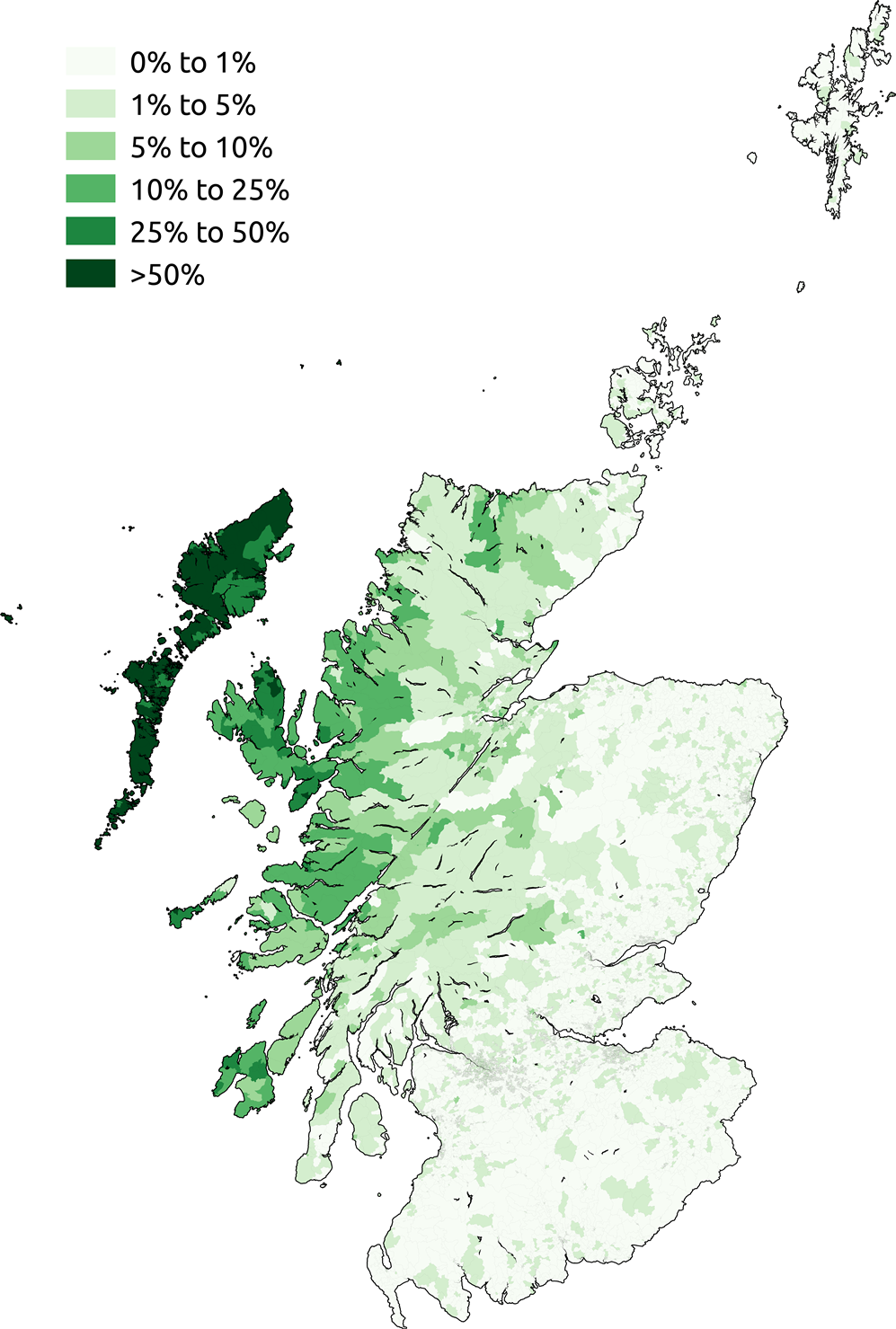

The proportion of respondents in the 2011 census aged 3 and above who could speak Gaelic.